"This course has helped train my eye and my mind to see more emotions in others, and as a result, have more successful interactions with others when they are emotional. I am more likely to notice things earlier, before escalation, when the potential to make better choices is stronger."

Read MoreLook Up

This video caught my attention because it is sending a message about the importance of our most basic form of communication; face-to-face. Our richest source of information about others comes from 5 channels, face, body language, voice, verbal style and verbal content.

Look Up starts with a poignant few words "I have 422 friends, yet I am lonely." In a nutshell the 5 minute video is summarized - yet it conitnues for another 4:55 making its case for why we need to look up and prioritize human, face-to-face interaction.

At 0:09 as Gary Turk, writter and performer in the video says "none of them really know me" watch the facial expression that follows. Interesting timing for the unilateral smirk (universal signal for contempt). As we know with facial expressions of emotion, we can tell what a person is feeling but we do not necessarily know why. Context helps to fill that gap and narrow down the hypotheses for behavioral clues. This is why probing into the why is just as important as observing and noticing sublte cues such as micro and macroexpressions that people give off.

Social Intelligence? There is a science for that.

When we think about the people in our lives we typically do so in terms of questioning the past or trying to predict the future. We wonder why we behaved a certain way or imagine how someone will react to news. The present however, is often elusive. That's because we don't have the capacity for deduction in-the-moment. We're not movie cyborgs equipped with millisecond data analysis in our periphery. We can't evaluate while we're in the process of real-time interaction. Well that's what we've thought. But what if our brains were actually conducting real-time analysis and feeding us data through our emotions? That is the crux of what Malcolm Gladwell described in "Blink" as "rapid cognition".

Humans developed a rapid cognitive process through which, for instance, we recognize signs of danger before we begin consciously deciphering what we see, leading to the often misunderstood notion that we possess extra-computational powers of observation, or a 'sixth sense'. Gladwell's work helped to demystify "thinking without thinking" related to external stimuli. In addition we are learning from the scientific community that this snap-perception capacity of humans is also present in social interactions. We use them in every situation from the mundane to the romantic to the dangerous.

Daniel Goleman explains our ability to very quickly 'get' an interpersonal exchange in his book "Social Intelligence", which details the study of social neuroscience. As an example Goleman reports; when a woman, who a man finds attractive, looks him directly in the eye, that non-verbal exchange triggers the release of dopamine in the man's brain. (Dopamine is a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure.) There is a measurable physiological reaction to the eye contact. This is because, as Goleman explains, "This science tells us our brains are mainly designed to connect to the brains of other people."

Our capacity to recognize the essence of a situation is not limited to (cue the music) "when we see a stranger across a crowded room". Our brains can detect hundreds of nonverbal messages in others which trigger emotional and physiological reactions in our brains and bodies. So why don't we act upon what we're feeling? The problem is we tend to think too much. We rationalize our feelings (perceptions) as emotional and therefore invalid because we've been taught that emotion and logic are mutually exclusive. The truth is emotions are integral to effective human behavior, not in conflict with it.

The better approach is to learn to recognize emotions, understand their triggers and train ourselves to discern the truth - to increase our social/emotional intelligence through training and practice.

Although we perceive and react to stimuli in a sort of subterranean cognitive process, the action happens so rapidly we don't notice it on a conscious level. We react to it on an emotional level - what we do unconsciously during that process is counter with shifting body language or we leak out our feelings through micro facial expressions. These movements create a reaction in the other person and the cycle continues in a constant loop.

Events happen in totality and with good reason. Our survival depended upon understanding the biggest possible picture in the shortest period of time. Our brains evolved to help us consolidate so for example, we don't separately remember potatoes, salad and chicken; we remember dinner. This same ability can make social interplay complicated. It's only after a conversation or some other exchange that we disaggregate the collective aspects of the event, often second-guessing our actions and reactions.

We don't need to have these low-grade regrets. The science of social intelligence tells us we can slide the description of human interaction from the complicated to the complex, making it less cosmic and more deductive.

The goal is to understand the science of human interaction, to learn how emotions drive behaviors and to learn to recognize emotions in ourselves and others so that "in the moment" we can understand what is transpiring. We can learn to embrace the good in a situation and be wary of what is less so. You will be astonished by what you see once you know what to look for.

Emotions; the antithesis of soft and fluffy

As part of success in working life is our abilities to build, maintain and grow relationships with others. Often this begins with a first meeting; maybe in an office, at a networking event or just socially. How well we as individuals manage that interaction is important.

I was talking to someone recently and they asked me that often dreaded question of "so what do you do then?"

The whole idea of an 'elevator pitch' bothers me a little and yet there are practical elements that can be of use. In my best succinct response I said "I specialize in emotions and their impact on people and performance." Feeling quite proud of my 11 word response I was met with a reply that triggered an emotional response in me, the emotion in particular was anger, only mild anger, maybe more frustration and triggered all the same.

This is important as the classic cliche says; 'you never get a second chance to make a first impression'.

If we are to navigate this initial meeting successfully, how aware are we of which emotions we may be experiencing and what called them forth?

So, what was said that got my 'hackles up' and triggered this wonderful orchestra of mental and physiological changes that we call an emotion. It was:

"Oh, so you do the soft and fluffy stuff then!" *followed by a short giggle*

Bearing in mind I am painting myself as someone that specialises in emotions it is good that a) I am already aware that this is a trigger of mine and b) that I can manage my responses to choose an action that will harness the emotion in a constructive (rather than destructive) way.

One thing that is really important to me is taking every opportunity to increase awareness of emotions in general and/or their impacts on individuals. So I decided to seize this opportunity while it presented itself. To begin, the anthropological angle.

It is commonly said that there are 3 principal drivers for the human species:

1) To survive

2) To eat

3) To reproduce

Confirming that this is something he was familiar with, I said that it is interesting that the 3 drivers of our species can (and regularly are) trumped by emotion. Met by a confused face I decided to elaborate. The will to survive can be overcome by extreme sadness or despair and end in suicide. The drive to reproduce can be paralysed by fear meaning little or no intimacy. If we perceive the food presented to us to be disgusting we will starve instead of eating it.

There are many more possible examples and yet all three of these show how emotion can be more powerful. To me, emotions are the exact opposite of soft and fluffy.

I went on to explain that if this is the impact emotions can have on our primal motives what about more day to day stuff like our relationships at home, or at work? That is where I help those I work with.

Increased awareness + strategies to manage responses = better choices and improved performance

Maybe I should say that instead next time?

What are your thoughts on emotions?

How do you see, hear or feel them affecting you?

If you want to read more about emotions and how I see their impact in the workplace please visit my blog http://e3ctc.wordpress.com/. You can also follow me on twitter @philwillcox. Or if you want to visit my website it is here www.e3ctc.co.uk.

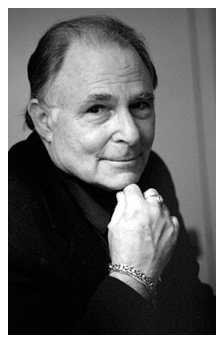

Dr. Paul Ekman gives commencement speech at Alliant University

This week we thought we would share with you the commencement speech that Paul Ekman, PhD., gave to the graduating students at Alliant University last June. In this short but powerful speech, Dr. Ekman shares his stance on trust - we all have a choice whether to trust or distrust, both carry a risk but one offers more happiness and even a longer life span. And, Dr. Ekman discusses the very important gap in our emotional response system between impulse and action that, if managed, can turn a regrettable emotional reaction to one that is constructive and beneficial. If you have pondered your position on trust or wondered how you can change how you act or what you do when you become emotional - read on as there are great words of wisdom imbedded in this speech.

This week we thought we would share with you the commencement speech that Paul Ekman, PhD., gave to the graduating students at Alliant University last June. In this short but powerful speech, Dr. Ekman shares his stance on trust - we all have a choice whether to trust or distrust, both carry a risk but one offers more happiness and even a longer life span. And, Dr. Ekman discusses the very important gap in our emotional response system between impulse and action that, if managed, can turn a regrettable emotional reaction to one that is constructive and beneficial. If you have pondered your position on trust or wondered how you can change how you act or what you do when you become emotional - read on as there are great words of wisdom imbedded in this speech.

"Let me add my congratulations for what you have achieved. It is a major milestone, perhaps the largest milestone in your work life. I passed such milestone in 1958, when I received my PhD in clinical psychology from Adelphi University. Looking back over 55 years I have thought about what I can tell you that I would have wanted to hear when I was in your shoes, at the beginning not the end of a career.

When I got my PhD I would never have predicted I would become a researcher rather than a private practitioner. Like many if not most of you, I wanted to be of help to a world in crisis, to help the many people suffering psychologically. Through a series of accidents I found that I could achieve that goal - relieving psychological suffering - through research more effectively than I could through practice. It was a better use of skills I didn't know I had, much to my surprise. I will return to this issue near the end of my talk - be open to surprises, surprises you discover about yourself.

I want to pass on to you some lessons I learned from the two research areas I spent my life studying - emotion and deception. These are lessons that don't appear in the journal articles or books, lessons about living your life. First a lesson about lying and truthfulness.

You have a choice which I hope you will make deliberately, consciously. The choice is what stance to take in your life about trust, in both your professional and your personal life. Should your stance be to trust that people mean what they say, or should you be more cautiously suspicious of what people say? Each stance has an attendant risk. I urge you to take the stance of trusting people whether they are friends, lovers, or patients. (Hopefully not all three at the same time in the same person). If your default is to trust, to take people at their word, even though we all know that anyone can make nearly anything up, you will be happier and probably live longer. But you will be taking the risk of being bamboozled. You will be a sucker for anyone who wants to exploit you.

You can avoid that unpleasant outcome by being distrustful and suspicious of everyone. You will be less happy, your life may be a bit shorter, and you take a different risk... you risk disbelieving a truthful person. You will have few friends, and lead a more guarded life. Unless you are working in law enforcement, or a related field, risk being misled, trust people. Even those in law enforcement should adopt that stance in their personal life.

My second area of research started with the facial expressions of emotion.

The evidence I found in the highlands of New Guinea helped to establish the universality of expression - all peoples share the same facial expressions of anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, enjoyment and contempt. Darwin predicted it, Margaret Mead couldn't believe it, and the Dalai Lama rejoices in this common link between all peoples. And yet we don't all experience these seven emotions the same way... there are differences in both the hardware and the software, if I can use that metaphor, for how emotions play out in each of us.

When people find out I study facial expressions of emotion, they worry I can read their thoughts, know their secrets. Once reassured that I can only read their feelings, even the feelings they are trying to hide (but I don't mention that) I get asked two questions: How can I change what I become emotional about? And... How can I change what I do, how I act when I am emotional?

It isn't easy to do either, nature doesn't want you to be consciously mucking around, choosing when to become emotional, or how to act when you are in the grip of an emotion. The emotion system evolved to deal with problems recognized and acted upon in an instant without conscious thought. Consider for a moment what would happen if you had to think what to do in order to avoid a near miss car accident, the current equivalent of the sabre tooth tiger. Consciousness, consideration, choice comes in usually late in an emotional episode, or after it is over. But there are work-arounds!

My last psychotherapy supervisor Frank Gorman at what was then called the Langley Porter Clinic (now Neuropsychiatric Institute), told me in 1957...'Paul if you can increase the gap between impulse and action you will have helped your patients enormously.' He should have added: for some people that gap is pretty wide, so it will be easy for them to learn how to recognize the impulse when it arises, decide whether to engage, and if so how to engage emotionally. While for others that gap is pretty small, it is very hard for them to become aware that an impulse to act emotionally has begun.

You already know which you are... a slow burner or a hothead, and I don't mean just about anger. If you are slow to anger my research has shown you are probably slow to get afraid, slow to become sad. And if you are fast to anger, you experience those other emotions very quickly. That is part of what I am calling your emotional profile.

All of us have emotional episodes in which we regret how we acted. Step 1 in the workaround is to make a list of those regrettable episodes; write them down in a diary every time one happens. At the end of a month or two read them through and see what is the common thread, what is the trigger that sets off regrettable episodes. There will be one. You need to find it, and once you do you can anticipate when one is about to beset you and prepare yourself. A totally different approach which can help increase the gap between impulse and action is to regularly adopt a contemplative practice for 20-30 minutes every day. It is a lot of work, but it does work, there is increasing research evidence showing the benefits of meditation.

The well-known Israeli novelist Amos Oz in his autobiography wrote about a lesson he learned from his aunt which I want to pass on to you. We are all dealt a different hand of cards. You didn't choose the hand that was dealt to you, you didn't choose your parents, your genes, how you were brought up, what you learned and didn't learn. That was all dealt. Find out what is in your hand: find the strengths and the weaknesses. That is step one. The wise aunt told her nephew some people play a terrible hand very well, and others play a great hand badly. It is up to you; you didn't deal the hand but you play it. At your age believe that you have a choice how you play it. Later in life you will find out there wasn't as much choice as you thought there was, circumstance and luck play a role. For now, learn what is in your hand and be great player of the hand you were dealt.

And remember why you obtained your education - never lose sight of how you can make a difference in the lives of others.

Be open to surprises; let accidents, ones of good fortune, especially, change your life. Find out what your best skills are... you probably don't yet know that but you will be finding out in the next few years. You are skilled as a student... think of how many years you have played that role. Now that role is over.

Act as if you are in complete control.

Play the deck you were given well. Know what that hand is."

(Dr Paul Ekman - June 2013).

The Upside of Deception

Human emotions are present in the nucleus of most every lie. Learning to understand them (Emotional Intelligence) and recognize them (Emotional Competency) are the lever and fulcrum of revealing lies and more importantly, uncovering the truth. It's not enough to know that a deception has occurred; in order to move forward, we must know the truth.

Not every lie is told with malice. Not every reason to hold back is rooted in wickedness or a compelling need to remain in the dark with one's deeds.

Indeed, some lies are necessary to save lives. A commander would not admit to having a plan in place to infiltrate a terror organization or attack enemy combatants. That type of knowledge in the wrong hands could lead to a preemptive strike by the terrorists against the interests of that nation and possibly cost the lives of civilians. So in this scenario the truth is kept purposely hidden and some might argue there is a moral imperative to do so.

Some lies are told to save the life of the liar. A young man escaping Nazi Germany would not be faulted for denying his faith, if only to survive long enough to get to a better position from which to defend it, or simply to save his family.

Lies are told to keep someone hopeful who may be distraught over a gravely ill family member. Lies are told to retain friendships, avoid conflict or shield someone from unnecessary stresses. Many a grandparent has been kept in the dark about a grandchild's arrest or accident until the situation is resolved and normalcy restored. It's the 'no harm - no foul' rule. The list of situations in which it may be argued that it is permissible to lie is as complicated as the human needs for acceptance, trust, peace of mind or a little more time.

Given that there are so many circumstances dictated by environmental pressures about which information must be misrepresented and sometimes omitted, and so many ethical arguments about whether or not telling lies of any kind is appropriate, we will focus on those instances when we must engage in difficult conversations. They may be work-related or personal but they somehow affect the future of the place where you stand and the people with whom you share that place.

Human interaction is often challenging and confusing. You would think we'd be better at it by now. We've been at it for thousands of years. We've developed intricate languages, symbols and facial expressions to communicate our thoughts. But instead of feeling gratified, interacting with our own species leaves us unsatisfied, frustrated, even exasperated. We feel shortchanged, unconnected or distant. When the truth is repressed, barriers to effective engagement are even more difficult to overcome.

The truth is usually known to one party and suspected by another. It does, after all, exist. The challenge is for both parties to feel comfortable with arriving at a common perception of the truth regardless of its consequences. It's about the desire to be open and the willingness to accept it. It's about mutual trust and the utility of honest communication. The point is not to judge the merits of the true thing, but merely to acknowledge it. It's a better place to start.

What keeps someone from expressing the truth is a feeling or presumption that the revelation will somehow degrade the relationship, perhaps irreparably so. They often want to be honest but feel they cannot or should not. For one reason, real or perceived, the one holding on to the truth is tangled in the vines of deceit. The real truth is inexorably tied to one emotion or another: anger, fear, joy, sadness and many more. It is precisely those emotions which we must look toward as the guideposts to truthfulness.

The listener must learn to observe the underlying emotions pressing themselves against the glass like a beggar at an upscale restaurant, silently pleading to be let in, or let out. The listener must look past what is obvious and ordinary, so they can see the waif in the window and recognize it for what it is, to let it in, accept it, feed it, respect it and move forward.

Elearning! Magazine December 2013 /January 2014 Issue

In August of 2013 People Intell had the privilege to speak at the Enterprise Learning! Conference and Expo held in Anaheim, CA. Our session was entitled "Lie To Me: The Science of Emotional Skills and Deception." We are happy to share with you our article that is featured in the December issue of Elearning! Magazine.

The Benefits of Truth within Leadership

The stakes are high. The truth is critical. What can you do to uncover it?

This denouement can play out across the spectrum of personal and professional human interactions. Just reading the words can trigger anxiety as you replay a time in your life when something mattered, when verity determined the difference between the winners and the also-rans.

Leaving aside the existential question of what truth is; we think we know it when it is before us in our everyday lives and we think we know when it's imperfect.

Truth is predicated on emotion. How does she really feel? What is his agenda? Is he listening to me? What is going on here that doesn't feel right? Why do they seem upset and where do we go from here? Why don't my employees communicate with me? How do I determine the truth?

The first step in finding the truth is to understand that emotions, those we reveal and those we try to suppress, are the drivers behind the behavioral and physiological manifestations that in some cases set off our internal alarms alerting us that something is amiss. We can learn to identify and interpret these cues more consistently and reliably to help us evaluate truthfulness.

The more you consider the possible applications for this skill, the more broadly you can relate its uses. To name just a few; imagine yourself managing a difficult team, hiring for a critical position, conducting an internal investigation, choosing a financial advisor, dealing with a complicated family matter, meeting new clients, or assessing the reaction of a focus group to new products.

This article is not about lying in a toxic sense but about the benefits of uncovering the truth of a situation. It's about personal or professional relationships and our ability to engage friends, employers, staff and counterparts honestly, perceptively and effectively. A person may have misgivings about absolute truthfulness for benign reasons. They may elect to mask their true feelings out of a sense of decorum, social norms, an unwillingness to hurt another's feeling, or as guided by context. The concept of dishonesty isn't always about trickery or malice.

The ability to discern the truth in a given situation has obvious advantages, but as a leadership trait, can be invaluable. A leader has the ability to recognize and manage not just his or her own emotions but also those of coworkers, competitors and employees. Executives with leadership presence have been shown to have high emotional intelligence or EQ, as outlined by Daniel Goleman in the Harvard Business Review.

How are emotions tied to deception and why are these concepts so inexorably linked? The full answer extends beyond the limits of this article but in short emotions tell us what matters, and the aforementioned is communicated in the form of expressions on our faces sometimes willingly and other times unwillingly with the world around us. Whether it is expressed openly, implied or repressed such as in the form of micro facial expressions, the cues are almost always there in front of us. Sensing it, recognizing it and functioning within the emotional underpinnings of it are crucial leadership skills. So how can we acquire or improve upon this ability?

We can learn the science of detecting the truth. Emanating from over 40 years of scientific research paired with real life application has illuminated that 5 channels of communication through which people express thoughts and feelings are key in detecting truth and assessing credibility. Underlying the 5 channels (face, body, voice, verbal style and words) is each individual’s baseline. In the context of deception, establishing a baseline is paramount. The baseline is how someone acts, reacts, speaks, gestures and generally interacts with others when they are in a relaxed state, unencumbered by a need to be deceitful about anything, irrespective of motivation. It's how they smile, stand, animate their faces, express ideas or move their hands when they speak. The trained observer, the leader, will be the one who recognizes what's swimming in the undercurrent. The person who understands how emotions instigate actions will bring the truth to the surface. It's why engaging coworkers is so critical to the success of your company.

How can you acquire what some have called "the leadership skill of the 21st century" and why is it so important to understand the science of deception?

"The ability to accurately detect deceit is real," says Paul Ekman, PhD, UCSF professor of psychiatry and principal investigator of a study published in Psychological Science in 1999. Ekman, who has been a leader in this field for decades, was able to demonstrate the role emotions play in deception. They are as inseparable as the water and the wet.

We can improve our odds by developing an understanding of the underlying emotions that precipitate deceptive behavior. The point is not to know the motivation for the deceit, but to know that it exists and to divine the truth which is often folded into emotion. The real goal is not to catch someone in a lie, but to elicit the truth about the situation in an engaging, intuitive, non-confrontational manner that serves the interests of all concerned.

Most importantly, emotional competencies will help managers bring employees back in to the fold, to make them feel a bigger part of the overall success of the mission. Harvard Business Review recently published findings from a Gallup survey that revealed up to 70% of workers are not engaged, meaning they simply don't care or are downright hostile towards employers. Although there are a host of reasons for this attitude, poor emotional intelligence by managers, directors and c-suite leaders prevents them from engaging employees positively, as part of the culture, rather than negatively, as in the dreaded performance review.

Wouldn't it be more efficient to avoid problems in the first place? Wouldn't employees who believe what they do matters be more likely to give a little extra, alert management to problems, interact with staff in a more honest way? Answer this simple question. Which mindset produces better results, a disengaged workforce or one that is self-determined, informed, worthy and relevant in the process?

Improving proficiency in two areas will propel you to a level beyond simply having people skills: emotional competence and detecting deception. With the right training, you can be the one person in the room who can navigate the ebb and flow of emotions, the one who can spot a flash of contempt, happiness, fear, anger, cynicism, sadness or other 'tells' that what someone is feeling is not what they are telling you. By learning to recognize the hidden emotions that leak out through non-verbal cues and micro-facial expressions, you can draw the honesty out of nearly any situation.

Why You Can't Spot Lies

"I knew he was lying all along; I should have trusted my gut."

"I knew he was lying all along; I should have trusted my gut."

Who hasn't said something like this after looking back at a situation, whether professional or personal? Once the whole truth has been revealed we like to reconstruct the events and look for the 'aha' moment that confirmed our suspicions. Once we know the lie we like to think we knew it in the moment. But did we really? Hindsight isn't always 20/20.

According to the scientific data, most of us aren't much better at detecting lies than flipping a coin, roughly 54% (Bond and DePaulo 2006). So what makes us so sure after the fact?

Let's back up. Although there are many complicated reasons why we may miss the truth, such as circumstances, limited process time, and our expectations about the outcome, there are cognitive biases that influence our tendency to accept what we've been told as the truth. Here are just a few:

· Visual Bias - the tendency to place more emphasis on visual clues than linguistic or inflection, tone and other auditory influences.

· Truth Bias - the tendency to overestimate other's truthfulness.

· Demeanor Bias - the tendency to judge another's communication style as being honest.

Our innate biases make it particularly difficult to detect lies in those we are closest to, which may seem counter-intuitive until you consider just two factors:

· The stakes are often higher in personal relationships (cheating spouse, teen drug user) so, given the possible consequences, we want to believe the other person.

· If we love the person we tend to give them the benefit of the doubt.

To detect dishonesty you must understand that emotions are the drivers of certain behaviors. Sometimes people are open and honest about their emotions and sometimes they attempt to conceal them. Yet, regardless of motivation, desire or reason - emotions rule!

Have you ever watched professional bull-riding? Those massive animals are constrained by a small pen, ropes, leather and a team of cowboys. They are bristling, coiled to break free and assert their alpha influence. Emotions are like bulls in the chute; they just need to get out and show themselves and they do so despite a person's best efforts to control them. They are conveyed through demeanor, voice, movement and especially through micro-facial expressions.

Emotions are most observable through the face. We can all picture or imitate a sad, angry, fearful or happy face, but we may not always want to show these emotions in a given situation. But in real interpersonal exchanges they can't be held back. So they leak out; they reveal themselves. They tell us the truth behind the facade. The problem is these expressions of emotion typically flash on and off the face so quickly (under 1/2 a second) we cannot see them with our conscience brain unless we know what to look for.

The good news is our brains are startlingly perceptive. The science of rapid cognition (Gladwell 2007) reveals that our brain sees these micro-expressions on a sub-conscious level and reacts to them. These reactions manifest themselves to us through our own emotions. So for example, the envious co-worker who wanted your promotion may congratulate you, but the disdain, disgust or anger they feel toward you is leaked out through a micro-facial expression. Your gut reacts. You feel awkward, uncomfortable, perhaps even angry and you aren't sure why. It's just something you feel.

So you thought he was lying all along? You were probably right. You just didn't know why you knew. Until the whole truth was revealed you relied on visceral feelings and sensations.

The better news is we can learn to recognize deception and deceptive behavior. We can tip the scales in our favor, uncover dishonesty and yes, we have science in our corner.

To become proficient in detecting deception you must be trained through a continuum. Your training must help you attain a higher level of emotional competency. It should teach you to manage your own emotions. With this base of understanding you can learn how to prepare your conscious brain to recognize what your subconscious brain is already seeing. The clarity you gain will be like putting on a new pair of glasses.

The science of micro-facial expressions is about opening up your mind to the human condition; its strengths, frailties, biases and universal codes of meaning.

Image courtesy of ddpavumba at FreeDigitalPhotos.net